Putting the pieces of the evaluation prep puzzle together: the ToR and beyond (part 2 of 2)

Jul 03, 2023

There’s more to preparing for an evaluation than drafting the ToR

A well-written terms of reference (ToR) for an evaluation goes a long way towards assuring the quality of your program’s evaluation. In the first of this 2-part article series on preparing for an evaluation, we covered (a) the basics of evaluation and ToRs and (b) the structure and content of a well-written evaluation ToR.

All that ToR talk is well and good, but there’s much more to planning for and assuring a successful evaluation[1] than the ToR. In fact, the ToR isn’t even the first or most important element of preparing for an evaluation.

In this article, we’ll dive into some of the non-ToR-specific elements of evaluation prep that can make or break an evaluation.

Non-ToR-specific elements that facilitate the success of an evaluation

Clarity and broad agreement on the purpose(s) of the evaluation

It should be pretty obvious as to why it’s important to have clarity and broad agreement on the purpose(s) of the evaluation, but it might be useful to explore the reasons anyway.

The purpose of the evaluation informs all the evaluation-related activities. Without clarity on the purpose, those served by the program, program team members, funders, and others may, between and among them, have different ideas about the evaluation’s purpose and how its findings will be used. This could lead to a myriad of problematic issues, with bearing not only on the planning of the evaluation but also on the implementation of, and follow-up on, the evaluation. No surprise then that “deciding what you want to learn from [the] evaluation…is the most important step in the process” (Child Care Technical Assistance Network (CCTAN), undated).

The ideal way in which to arrive at an agreed purpose of the evaluation is in consultation with all relevant parties.* Together, “[c]onsider what is most important to discover about your program and its impact on participants, and use this information to guide your evaluation planning” (CCTAN, undated). In this manner, broad agreement can be gained in the process of gaining clarity on the evaluation – rather than first deciding on what the purpose is and then getting everyone to agree. A word of caution, though: “When [program teams and stakeholders] brainstorm about the questions they want answered, they often produce a very long list. This process can result in an evaluation that is too complicated. Focus on the main purpose of the evaluation and key questions that it should address.” (CCTAN, undated)

(*Which parties are ‘relevant’ will depend on your program and its specific context. If stakeholder mapping was done in earlier stages, that map would be a good place to start for identifying who should be consulted with; if not, use the evaluation planning as an opportunity to do such mapping.)

A competent and empowered evaluation manager

Designating a competent member of the program team as the lead for managing the evaluation helps ensure that the necessary evaluation planning, implementation oversight, and follow-up processes occur as they should. Essentially, just as the purpose of the evaluation informs the evaluation-related activities (as discussed above), the evaluation manager becomes the “engine driving [those activities]” (McMillan D. and Willard A., 2008).

The evaluation’s manager will often be a member of the program’s M&E team. But whoever she or he is, “[this person] needs a clear understanding of the process or a commitment to learning the process. The evaluation manager is responsible for ensuring that specific pre-evaluation products (core project documents, updated information on indicators, and so on) are presented in a timely manner.” (McMillan D. and Willard A., 2008) She or he will also need to manage the process of processing the evaluator’s deliverables (receiving them, distributing them among reviewers, ensuring that consolidated feedback is provided to the evaluator and followed up on, etc.) as well as carry out secretariat function to the evaluation taskforce (see below), if the program chooses to put one in place.

These functions that are central to an evaluation’s success, and the evaluation manager should be capable of, and empowered to, carry out.

Solid understanding of funder-specific requirements and the program’s own principles

Your program’s funders may have specific requirements related to program evaluations, and it is important that these expectations be understood and taken into consideration in evaluation planning so that the program’s funding is not unnecessarily placed at risk.

For example, “[a]s part of their standard guidance for proposal writing, most donors provide a brief explanation of what they expect in a mid-term or final evaluation as well as for routine M&E.” (McMillan D. and Willard A., 2008)

Not to say that funder conditions can’t be changed! If called for, the program team should engage in a discussion with the funder on any requirements that run counter to the program’s context (including, but not limited to, the culture in which the program operates) or research ethics.

This discussion will help inform the broader guiding principles and research ethics or procedures to be followed in the conduct of the evaluation.

In the context of inclusive social/international development, it is highly likely that one of those principles will be ‘to be aware of and sensitive to cultural issues’, with the ethic of respecting and protecting community members, viz.:

“When evaluating a program…, always consider the responsibilities to the participants and the community. You must ensure that the evaluation is relevant to and respectful of the cultural backgrounds and individuality of participants. Evaluation instruments and methods of data collection must also be culturally sensitive and appropriate…[and] participants must be informed that they are taking part in an evaluation and that they have the right to refuse to participate in this activity without jeopardizing their participation in the program. Also, ensure that confidentiality of participant information will be maintained. Knowing when to use an Institutional Review Board is also important. This is an administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects who are recruited to participate in research activities that are conducted under the sponsorship of the institution with which it is affiliated.” (CCTAN, undated)

Understanding of, and in-principle agreement on, likely methodological approaches to be employed

After the purpose of the evaluation has been defined and agreed upon and its guiding principles and ethics established, options for the evaluation’s approach and methodology will likely start to emerge. It may even be that a single methodological approach reveals itself as the obvious choice.

However, this does not need to be decided and laid out at this stage – in fact, the evaluation approach and methodology will only really be finalized once the selected evaluator has submitted the related deliverable. Nonetheless, it may be worth starting to consider the implications of the various approaches not only on the obvious matter of fulfilling the evaluation’s purpose, but also on the level of effort and profile required of the evaluator and of various stakeholders who will be engaged, to varying extents, in the evaluation’s implementation.

Doing so will help keep expectations are realistic and sustain buy-in and commitment. Speaking of which….

Sustained buy-in and commitment from all relevant stakeholders based on a realistic understanding of the burden on the program team and on respondents to evaluation-related data collection exercise

For an evaluation to succeed, it needs broad-based buy-in and commitment, with the requisite participation and engagement. This needs to especially come from the program’s leadership – “[l]eadership involvement will encourage a sense of ownership of and responsibility for the evaluation among program staff” (CCTAN, undated) –, from the funder, from members of the population that the program serves. In my experience, the greater the extent of engagement with the evaluation, the greater the value gained from it. Ensure that the engagement is meaningful by, for example, including members of different stakeholder groups in the evaluation’s management structure (see next sub-section).

To circle back to the earlier point made about expectations, an important aspect of ensuring sustained participation and engagement is to make sure that everyone shares an understanding of the burden that conducting the evaluation will place on their shoulders, according to the role they play. It’s critical to not underestimate the effort that it takes to commission, manage, conduct, and follow-up on an evaluation, even when the evaluation itself will be conducted by an external entity. Even a seemingly simple task such as arranging for the evaluator to have access to records can take a substantial amount of time.

An inclusive evaluation management structure – with its own ToR!

Putting an evaluation management taskforce or board in place, composed of good representatives from various stakeholder groups, is a helpful way to ensure meaningful, broad participation in the planning, implementation, and follow-up on the evaluation. This taskforce should have its own ToR – not to be confused with the evaluation ToR! – that unambiguously articulates its scope of work, notably clearly laying out what taskforce members will do and how they will do it.

The taskforce’s brief will vary from evaluation project to evaluation project but will likely, at a minimum, include:

- discussing and finalizing the evaluation ToR (the first draft of which would be prepared ex ante by the evaluation manager or other appropriate person/team);

- review and discussion of the evaluator’s deliverables; and

- agreeing on a plan of action to implement any recommendations arising from the evaluation.

The taskforce’s brief will inform the section of the evaluation ToR that articulates the evaluation’s governance, management, and coordination arrangements (see part 1 of this article).

___

A BRIEF ASIDE ON THE SEQUENCING AND CHRONOLOGY OF THESE NON-TOR-SPECIFIC ELEMENTS:

Though the sequencing for ensuring that the above elements are in place can be somewhat fluid, they should ideally all be in place before the ToR is drafted. On the other hand, the elements that follow below can be put in place after the ToR has been published up – even up until the kick-off meeting with the selected evaluator.

In terms of when overall evaluation planning should start – well, as early as possible. This will maximize the amount of time available to incorporate the evaluation into ongoing program management and potentially even undertake some or all of the necessary data collection exercises.

___

Well-organized program documentation for the evaluator’s document review

In the early stages of evaluation implementation, the selected evaluator will very likely need to conduct a review of core program reports and other key project-related documents. Organizing these well enables the evaluation team to start work faster (McMillan D. and Willard A., 2008) and proceed efficiently. Building a program or project “bibliography” (McMillan D. and Willard A., 2008) is a good strategy for ensuring a comprehensive, well-organized set of core program documents.

Well-planned evaluation logistics

McMillan D. and Willard A. note that “[i]f logistics are poorly thought out and funded, even the best evaluation team will not be successful” (2008). This has proven to be true in my experience. To ensure successful evaluation implementation, a detailed logistics plan should be drafted, and its execution competently coordinated.

The specifics of the logistics plan will vary from evaluation project to evaluation project, but a likely important element of most logistics plans will be pre-planning for field-based data collection (surveys, key informant interviews, participant observation, etc.), which may require formal permission letters from the national or local government or other duty-bearers as well as public announcements and other messaging – in the appropriate language of course.

We’re not done yet: a couple additional elements that facilitate the planning and implementation of a successful evaluation

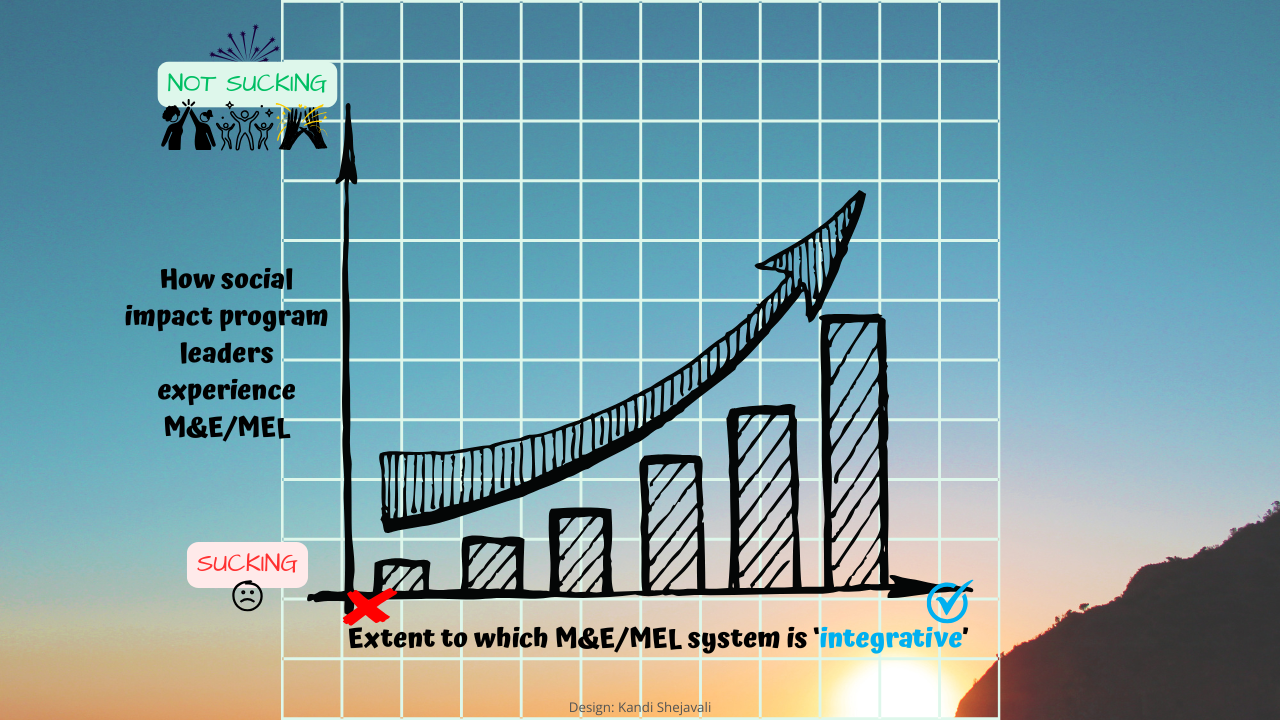

An existing fit-for-purpose M&E system

If your program has a fit-for-purpose M&E system in place, it will go a looong way towards ensuring the smooth planning and implementation of the evaluation. How so? In so many ways! To name just a few:

- the objectives and principles of the M&E system will help inform those of the evaluation;

- the theory of change (ToC) will be robust, serving as an enormous aid to the evaluators;

- a significant degree of stakeholder buy-in will already be present, meaning you won’t be starting from zero when extending such buy-in to the specific evaluation;

- the evaluation process will have already been integrated into the program’s ongoing processes and activities, easing the evaluation’s burden on the program team and minimizing the overall level of disruption – as well as enabling the program team to “gain knowledge and improve practice from an evaluation more quickly” (CCTAN, undated) (this alone is a huge win!);

- indicators and related data collection procedures will be well documented, yielding high-quality data that the evaluator can use, if relevant and appropriate, and thus also potentially reducing the cost of the evaluation, with the added benefit of helping enhance the degree of confidence and veracity of the evaluation’s findings.

And, and, and!

In short, having a solid M&E system in place reaps enormous rewards!

Readily accessible data to inform the evaluation and/or supplement evaluation-specific data collection

Another important piece of the evaluation preparation puzzle to have in place is readily accessible program/project data. These data should not only include M&E system-generated evidence but also administrative information, program/project financials (which are key for evaluation exercises that involve assessing value-for-money (VfM), for example), and various reports related to the program.

There are several options when it comes to strategies to adopt to ensure that all relevant information is readily accessible to the evaluator. For example, you could prepare a project activity briefing book that contains the program’s/project’s administrative history and organization and information on the financial systems, M&E systems and indicator updates, technical components, community/activity matrices, and maps (McMillan D. and Willard A., 2008).

Phew, that was quite a list! – let’s wrap up and then it’s over to you!

Beyond developing a well-written ToR, it’s critical to put several other important elements in place to pave the way to a successful evaluation. If you have an evaluation coming up for your program or project, get a head start by taking the necessary actions to put those elements in place. Along with the ToR, they’ll set you up well for an evaluation that truly achieves its objectives.

References:

Child Care Technical Assistance Network (CCTAN) (undated) Guiding Principles for Preparing for a Successful Evaluation. Web page. Available at https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/systemsbuilding/systems-guides/evaluation-and-improvement/preparing-successful-evaluation (accessed: 5 June 2023).

McMillan D. and Willard A. (2008) Preparing for an Evaluation: Guidelines and Tools for Pre-Evaluation Planning. American Red Cross and Catholic Relief Services. Available at https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/MEmodule_preparing.pdf (accessed: 5 June 2023).

Sridharan and Naikama’s article “Ten steps to making evaluation matter” at https://meghalayaevaluationschool.com/2022/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ten-steps-send-Ian.pdf

Photo credit:

Edge2Edge Media on Unsplash

Suggestion for how to cite this article (using APA 7 style):

Shejavali, K. (2023, July 3). Putting the pieces of the evaluation prep puzzle together: the ToR and beyond (part 2 of 2). Blog post. RM3 Consulting. Available at: https://www.rm3resources.com/blog/pieces-of-eval-prep-puzzle-part-2 (accessed: [insert the date that you last accessed this article at the link provided]).

[1] A ‘successful evaluation, can be defined as an evaluation that achieves its objectives within the given time, scope, and budget.